A simple data ETL method – nothin’ but SQL

My client has decided to design and build a completely new replacement system for an aging system running on Oracle Forms 6i on Oracle 8. The new system will have a web frontend, backed by Hibernate (don’t get me started) on top of an Oracle 11gR1 database. Crucially, due to changes to business practices and legislation, the new system has been designed “from scratch”, including a new data model.

My task is to write the ETL scripts which will take the data from the legacy database (an Oracle 8i schema), transform it to meet the requirements of the new model, and load it. If you’re looking at building scripts to transform data from one system to another, the method I used might be helpful for you too.

Making it more complicated is their desire that the data move be executed in two stages – (1) before the switch-over, transform and load all “historical” data; (2) at go-live, transform and load all “current” data, as well as any modifications to “historical” data.

Since the fundamental business being supported by this system hasn’t changed very much, the old and new data models have a lot in common – the differences between them are not very complex. In addition, the data volume is not that great (coming from someone who’s worked with terabyte-scale schemas) – the biggest table only had 2 million rows. For these reasons, the purchase of any specialised ETL tools was not considered. Instead, they asked me to write the ETL as scripts that can just be run on the database.

These scripts must be re-runnable: they should be able to be run without modification to pick up any changes in the legacy data, and automatically work out how to merge the changes into the new schema.

The first step for me was to analyse both data models, and work out a mapping for the data between them. The team for the project had a very good idea of what the tables in the new model meant (since they had designed it), but there was no-one available to me to explain how the old data model worked. It was down to me to learn how the legacy data model worked – by exploring it at the database level, examining the source for the forms and reports, and in some cases by talking to the users.

The outcome of this analysis was two spreadsheets: one was a list of every table and column in the legacy database, and the other was a list of every table and column in the new database. For each table in the legacy database, I recorded which table (or tables) the data would be migrated to in the new schema, or an explanation if the data could be safely disregarded. For each table in the new schema, I recorded which table (or tables) in the legacy database would feed into it. In the end, eleven of the tables in the new schema would be loaded.

Then, for each table in the legacy and new schemas, I worked through each column, identifying what it meant, and how it would be mapped from the old to the new. In some cases, the mapping was very 1:1 – perhaps some column names were different, or code values different, but relatively simple. In other cases, the mapping would require a more complex transformation, prehaps based on multiple tables. For example, both systems had a table named “ADDRESS” which stored street or postal addresses; in the old system, this table was a child table to the “PARTY” table; so PARTY was 1:M to ADDRESS. In the new model, however, there was a master “ADDRESS” table which was intended to store any particular address once and only once; the relationship of PARTY to ADDRESS is M:M. De-duplication of addresses hasn’t come up yet but it’s going to be fun when it does 🙂

Thankfully, in no cases was the mapping so complicated that I couldn’t envisage how it could be done using relatively simple SQL.

Once the spreadsheets were filled, I was finally able to start coding!

In order to meet the requirements, my scripts must:

- INSERT rows in the new tables based on any data in the source that hasn’t already been created in the destination

- UPDATE rows in the new tables based on any data in the source that has already been inserted in the destination

- DELETE rows in the new tables where the source data has been deleted

Now, instead of writing a whole lot of INSERT, UPDATE and DELETE statements, I thought “surely MERGE would be both faster and better” – and in fact, that has turned out to be the case. By writing all the transformations as MERGE statements, I’ve satisfied all the criteria, while also making my code very easily modified, updated, fixed and rerun. If I discover a bug or a change in requirements, I simply change the way the column is transformed in the MERGE statement, and re-run the statement. It then takes care of working out whether to insert, update or delete each row.

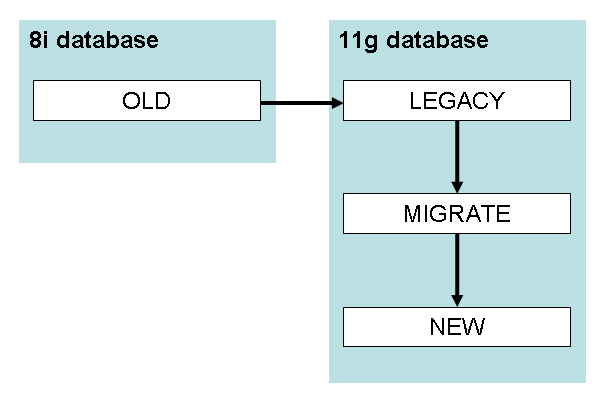

My next step was to design the architecture for my custom ETL solution. I went to the dba with the following design, which was approved and created for me:

- create two new schemas on the new 11g database: LEGACY and MIGRATE

- take a snapshot of all data in the legacy database, and load it as tables in the LEGACY schema

- grant read-only on all tables in LEGACY to MIGRATE

- grant CRUD on all tables in the target schema to MIGRATE.

All my scripts will run as the MIGRATE user. They will read the data from the LEGACY schema (without modifying) and load it into intermediary tables in the MIGRATE schema. Each intermediary table takes the structure of a target table, but adds additional columns based on the legacy data. This means that I can always map from legacy data to new data, and vice versa.

For example, in the legacy database we have a table:

LEGACY.BMS_PARTIES( par_id NUMBER PRIMARY KEY, par_domain VARCHAR2(10) NOT NULL, par_first_name VARCHAR2(100) , par_last_name VARCHAR2(100), par_dob DATE, par_business_name VARCHAR2(250), created_by VARCHAR2(30) NOT NULL, creation_date DATE NOT NULL, last_updated_by VARCHAR2(30), last_update_date DATE)

In the new model, we have a new table that represents the same kind of information:

NEW.TBMS_PARTY( party_id NUMBER(9) PRIMARY KEY, party_type_code VARCHAR2(10) NOT NULL, first_name VARCHAR2(50), surname VARCHAR2(100), date_of_birth DATE, business_name VARCHAR2(300), db_created_by VARCHAR2(50) NOT NULL, db_created_on DATE DEFAULT SYSDATE NOT NULL, db_modified_by VARCHAR2(50), db_modified_on DATE, version_id NUMBER(12) DEFAULT 1 NOT NULL)

This was the simplest transformation you could possibly think of – the mapping from one to the other is 1:1, and the columns almost mean the same thing.

The solution scripts start by creating an intermediary table:

MIGRATE.TBMS_PARTY( old_par_id NUMBER PRIMARY KEY, party_id NUMBER(9) NOT NULL, party_type_code VARCHAR2(10) NOT NULL, first_name VARCHAR2(50), surname VARCHAR2(100), date_of_birth DATE, business_name VARCHAR2(300), db_created_by VARCHAR2(50), db_created_on DATE, db_modified_by VARCHAR2(50), db_modified_on DATE, deleted CHAR(1))

You’ll notice that the intermediary table has the same columns of the new table (except for VERSION_ID, which will just be 1), along with the minimum necessary to link each row back to the source data – the primary key from the source table, PAR_ID.

You might also notice that there is no unique constraint on PARTY_ID – this is because we needed to do some merging and de-duplication on the party info. I won’t go into that here, but the outcome is that for a single PARTY_ID might be mapped from more than one OLD_PAR_ID.

The second step is the E and T parts of “ETL”: I query the legacy table, transform the data right there in the query, and insert it into the intermediary table. However, since I want to be able to re-run this script as often as I want, I wrote this as a MERGE statement:

MERGE INTO MIGRATE.TBMS_PARTY dest

USING (

SELECT par_id AS old_par_id,

par_id AS party_id,

CASE par_domain

WHEN 'P' THEN 'PE' /*Person*/

WHEN 'O' THEN 'BU' /*Business*/

END AS party_type_code,

par_first_name AS first_name,

par_last_name AS surname,

par_dob AS date_of_birth,

par_business_name AS business_name,

created_by AS db_created_by,

creation_date AS db_created_on,

last_updated_by AS db_modified_by,

last_update_date AS db_modified_on

FROM LEGACY.BMS_PARTIES s

WHERE NOT EXISTS (

SELECT null

FROM MIGRATE.TBMS_PARTY d

WHERE d.old_par_id = s.par_id

AND (d.db_modified_on = s.last_update_date

OR (d.db_modified_on IS NULL

AND s.last_update_date IS NULL))

)

) src

ON (src.OLD_PAR_ID = dest.OLD_PAR_ID)

WHEN MATCHED THEN UPDATE SET

party_id = src.party_id ,

party_type_code = src.party_type_code ,

first_name = src.first_name ,

surname = src.surname ,

date_of_birth = src.date_of_birth ,

business_name = src.business_name ,

db_created_by = src.db_created_by ,

db_created_on = src.db_created_on ,

db_modified_by = src.db_modified_by ,

db_modified_on = src.db_modified_on

WHEN NOT MATCHED THEN INSERT VALUES (

src.old_par_id ,

src.party_id ,

src.party_type_code ,

src.first_name ,

src.surname ,

src.date_of_birth ,

src.business_name ,

src.db_created_by ,

src.db_created_on ,

src.db_modified_by ,

src.db_modified_on ,

NULL );

You’ll notice that all the transformation logic happens right there in a single SELECT statement. This is an important part of how this system works – every transformation is defined in one place and one place only. If I need to change the logic for any column, all I have to do is update it in one place, and re-run the MERGE.

This is a simple example; for some of the tables, the SELECT statement is quite complex.

(Warning: you’ll note that I’ve omitted the column list from the INSERT clause; this can be dangerous if you’re not in complete control of the column order like I am for this particular table)

There is a follow-up UPDATE statement that for a couple of thousand records, changes the PARTY_ID to a different value; in effect, this performs the de-duplication.

Next, we look for any rows that have been deleted:

UPDATE MIGRATE.TBMS_PARTY dest SET deleted = 'Y' WHERE deleted IS NULL AND NOT EXISTS ( SELECT null FROM LEGACY.BMS_PARTIES src WHERE src.par_id = dest.old_par_id);

The idea is that the data in the MIGRATE table is *exactly* what we will insert, unmodified, into the target schema. In a year’s time, we could go back to this MIGRATE schema and see what we actually inserted when the system went live. In addition, we’ll be able to go back to the LEGACY schema and see exactly how the data looked in the old system; and we’ll be able to use tables like MIGRATE.TBMS_PARTY to map back-and-forth between the old and new systems.

The final stage of the process is the “L” of “ETL”. This, again, uses a MERGE statement:

MERGE INTO NEW.TBMS_PARTY dest

USING (

SELECT *

FROM MIGRATE.TBMS_PARTY s

WHERE s.party_id = s.old_par_id /*i.e. not a duplicate*/

AND (s.deleted IS NOT NULL

OR NOT EXISTS (

SELECT null

FROM NEW.TBMS_PARTY d

WHERE d.party_id = s.party_id

AND (d.db_modified_on = s.db_modified_on

OR (d.db_modified_on IS NULL

AND s.db_modified_on IS NULL))

) )

) src

ON (src.party_id = dest.party_id)

WHEN MATCHED THEN UPDATE SET

party_type_code = src.party_type_code ,

first_name = src.first_name ,

surname = src.surname ,

date_of_birth = src.date_of_birth ,

business_name = src.business_name ,

db_created_by = src.db_created_by ,

db_created_on = src.db_created_on ,

db_modified_by = src.db_modified_by ,

db_modified_on = src.db_modified_on

DELETE WHERE (src.deleted IS NOT NULL)

WHEN NOT MATCHED THEN INSERT (

party_id ,

party_type_code ,

first_name ,

surname ,

date_of_birth ,

business_name ,

db_created_by ,

db_created_on ,

db_modified_by ,

db_modified_on )

VALUES (

src.party_type_code ,

src.first_name ,

src.surname ,

src.date_of_birth ,

src.business_name ,

src.db_created_by ,

src.db_created_on ,

src.db_modified_by ,

src.db_modified_on )

LOG ERRORS

INTO MIGRATE.ERR$_TBMS_PARTY

REJECT LIMIT UNLIMITED;

A few things to note here:

- The SELECT clause brings back each row from the intermediary table that has not been merged to a new record (by the way, those records are needed because they are used when transforming PAR_ID values in child tables) or that has not been modified since it was previously loaded.

- The MERGE inserts any new rows, updates all columns for modified rows, and deletes rows that have been marked for deletion.

- NO transformation of data happens here.

- If any data fails any validation, the MERGE logs the error and continues, using a table created using this:

BEGIN

DBMS_ERRLOG.create_error_log('NEW.TBMS_PARTY',

err_log_table_name => 'ERR$_TBMS_PARTY',

err_log_table_owner => 'MIGRATE');

END;

I can then query this error table to see if there were any problems, e.g.:

SELECT ORA_ERR_OPTYP$, ORA_ERR_MESG$, COUNT(*) FROM MIGRATE.ERR$_TBMS_PARTY GROUP BY ORA_ERR_OPTYP$, ORA_ERR_MESG$;

A common issue is a failed check constraint, e.g. where the old system failed to validate something correctly. We’d then go back and either change the transformation to work around the problem, or send the data back to the business and ask them to fix it in the source.

Each stage of this ETL solution can be restarted and re-run. In fact, that’s what we will be doing; a few weeks prior to go-live, we’ll get a preliminary extract of the old system into the LEGACY schema, and run all my scripts. Then, at go-live, when the old system is taken down, we’ll wipe the LEGACY schema and refresh it from Prod. We will then re-run the scripts to take changes through.

All the scripts for each table had the same structure: one script to create the intermediary table; one script to do the merge into the intermediary table; and one script to merge into the final destination. With the exception of the SELECT statement in the first merge script, which differed greatly for each table, these scripts were very similar, so I started by generating them all. For this I used queries on the data dictionary to generate all the SELECT lists and x = y lists, and after a bit of work I had a complete set of ETL scripts which just needed me to go in and make up the SELECT statement for the transformation.

For this case, a relatively simple data migration problem, this method seems to have worked well. It, or a variation on it, might very well work for you too.

Connor

3 February 2011 - 10:07 pm

…backed by Hibernate on top of an Oracle 11gR1 database…

Well then – its a good thing you’ve written a flexible migration facility, because you’re gonna need it to migrate off the new system not too far off in the future 🙂

hee hee hee… Hibernate … good luck with that. The name is spot on though – it represents things frozen and moving very very very slowly…

But seriously, going with 11.1 is madness – the existence of 11.1.0.6, 11.1.0.7, 11.1.0.7.1, 11.1.0.7.2, 11.1.0.7.3, 11.1.0.7.4, 11.1.0.7.5 should be sufficient evidence of that !

Jeffrey Kemp

4 February 2011 - 6:46 am

I tried, I tried 🙂 maybe if we’re lucky they’ll decide to upgrade the db, not that they’ll see much difference from the app’s point of view…

I actually argued for either (a) putting the new schema on the same instance as the other databases with which it will need to interface, to avoid the need for database links – which would have meant it would be on 10g, or (b) at least install 11gR2 on the new instance. They did neither.

Life’s much better than it would have been if they’d stuck with the 8i database, at least.

Jeffrey Kemp

4 February 2011 - 3:33 pm

Scratch that – just realised the database is 11.2.0.1 – I don’t know why I thought it was R1 – maybe because the instance name is “DEV11G01”

mdinh

4 February 2011 - 2:50 am

Like to get your opinions if you have not already blogged about it on hibernate.

The pros and cons of course.

Jeffrey Kemp

4 February 2011 - 6:47 am

Someday, perhaps, I’ll write a blog post about that. But not today…

Thanks for stopping by 🙂

Gary Myers

4 February 2011 - 2:23 pm

Thanks for that.

What mechanism are you using for OLD -> LEGACY ?

Does it come down to old fashioned exp/imp ?

Jeffrey Kemp

4 February 2011 - 3:33 pm

The dba team here do it for me – they use exp/imp to get the data from 8.1.6 to 11.2.0.1.

Madura – SL

19 September 2013 - 3:20 pm

Fantastic no needed to expert knowledge to understand that the way u did. But…… you give me to hand to be a expert in BI & DWH future ……